The English Word That Hasn’t Changed in Sound or Meaning in 8,000 Years

Fun one!

Inspiration and encouragement for your own personal journey of awakening …

I love Mediterranean cuisine and when our weather here in Uruguay (Southern Hemisphere) changes from the hot days of summer into the cooler days of fall, into winter, I find myself wanting warm comfort food. The kind of dish that cooks slowly in the oven for hours (until the meat falls off the bone) with the sweet smell of rosemary, oregano, or wild marjoram wafting in the air, Mediterranean style.

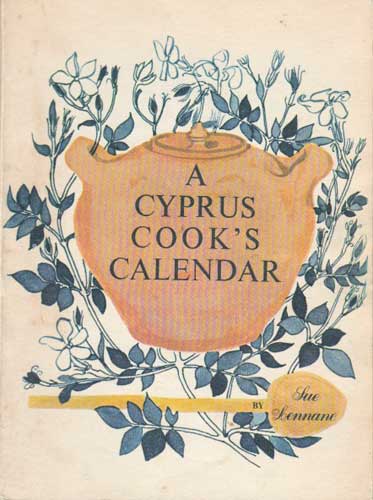

When I lived in Cyprus in the early 70s, I had a wonderful cook book titled “A Cyprus Cook’s Calendar.” It was written by a British writer, Sue Lennane, for the British Forces Broadcasting Service in Cyprus in 1969. A delightful month by month cook book, it provided recipes based on fruits and vegetables available and in season. I used it often and was sad to lose it, along with everything I owned, following the Cyprus War in July 1974.

Years later, while living in Frankfurt, Germany, a friend who was my neighbor in Cyprus, sent me a copy of the cook book (the original First Edition 1969). I was thrilled because it had so many of my best-loved Cypriot recipes in it.

One all-time favorite is a recipe for slow roasted lamb, called Tandir in Turkish and Kleftiko in Greek. Lamb Kleftiko, roughly translated, means stolen meat. Legends say that thieves would sneak onto a remote Greek hillside and steal a lamb or goat, and cook the meat for hours over coals in a hole sealed with mud to prevent steam escaping and alerting the shepherd who previously owned the animal.

In Cyprus, Kleftiko is cooked in a sealed earthenware pot with a narrow opening buried in the earth, with a fire under it, and left to cook very slowly for hours. Kleftiko pots are still sold in Cyprus. (See picture on the front cover of the cook book.) Since my Kleftiko pot was also left behind in Cyprus, I’ve reverted to using a large, deep casserole dish, covered with aluminum foil and a tight fitting lid.

Lamb Kleftiko (Serves 6)

Ingredients:

2 lb. lamb (a piece of leg or loin cut up)

salt and pepper

2 T. olive oil

oregano or wild marjoram

juice of ½ lemon

2 tomatoes, diced

1 cup red or white wine

1 large onion (peeled and cut into quarters)

1 T. peeled and chopped garlic

Preparation:

Place the meat and olive oil in the Kleftiko pot or casserole dish. Add the onion and garlic. Sprinkle with oregano, salt, pepper, lemon juice, and red or white wine. (A glass of wine is also recommended for the chef and any helpers.) Cover the top with aluminum foil and place the lid on top. Cook in a moderate oven, No 3, 325º, for 3 hours. Turn off oven and leave simmering for an extra hour.

Kleftiko is rustic, delicious, and finger-licking good. Serve over a bed of al dente pasta or rice. It’s extra delicious when served with eggplant ratatouille.

ENJOY!

Susan interviewed on Epicurious.com

Initially, the web site editor picked a photo of American barbeque to represent Uruguayan asado, which is almost sacrilege! (Quickly corrected when we pointed it out 😉

Apparently Uruguayans and Argentinians get great amusement out of seeing North American ads for “flame-grilled” steaks. In Uruguay and Argentina, flames never touch the meat. The wood is burned on the side, and the coals raked underneath the meat, which cooks at surprisingly low heat for a not-surprising long time.

You can see an explanation in this video, from 0:45 to 2:45.

![By Fedaro (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://peelbooks.com/susanjoycejourneys/wp-content/uploads/parrillero.jpg)

… unless you’ve got plenty of beer, friends, time, …

… and perhaps a Playstation and flat-screen TV ….

I was introduced to La Cuisine Seychelloise in August 1975, after a private yacht I helped crew docked in the port of Victoria, Mahe, Seychelles on the day after the Assumption Day festivities had ended.

By late morning we received clearance from the port authorities, and my husband and I were allowed to step ashore on the tropical paradise archipelago of the Seychelles. We had spent thirty days of mostly hellish weather in monsoon season crossing the Indian Ocean (from Sri Lanka to Diego Garcia) and another week of battering storms from Diego Garcia to the Seychelles. Physically and emotionally drained, we asked the English Captain to give us permission to disembark in Port Victoria. Knowing he needed crew to sail on up through the Suez Canal, he was reluctant to let us go. But knowing we were unhappy about the weird things happening on board between him and his crazy Israeli girlfriend (that’s another story!), he finally agreed to give us our passports and allow us to leave the yacht with our belongings. Prior to this adventure, I knew nothing about Maritime law and a captain’s supreme authority to do just about anything he wants, including not allowing passengers to leave the ship.

Grateful to touch solid ground again, I took a few deep breaths and shed happy tears. No more rubber sea legs, sea sickness, and no more being chained to the railing when working on deck. We had somehow managed to survive storm after storm, giant wave after walls of giant waves, and were now free to walk about on earth again. In paradise no less. Our first stop was the bank to exchange money. Next stop, lunch at a restaurant in the harbor! Real food? What a treat! Our eyes of course were bigger than our stomachs and we ordered more than we could possibly eat. We asked an Australian couple, dining at a table near by, for lodging recommendations. They immediately referred us to a private B & B owned by Eveline Man-Cham. “Her cooking is the finest,” the woman told me. “The country’s traditional cuisine. Creole cooking! You’ll want to eat there all the time.”

After lunch, and receiving numerous tourist tips from the waiters and other diners, we hired a taxi to take us to Mrs. Man-Cham’s place. We checked in and were given a snack of fried breadfruit cakes with afternoon tea. I oohed and aah-ed, and asked for the recipe. Mind you I didn’t have a clue what breadfruit was but Mrs. Man-Cham was happy to show me the breadfruit trees and explain the variety of ways the Seychelloise used it in cooking and baking. She invited us to join them for dinner before we left to explore the nearby beaches.

“I’ve prepared ladob patat for dessert,” she said as we were leaving. I obviously looked confused. She smiled and added, “sweet potato pudding.”

“Sounds delicious,” I replied. “We’ll join you.”

I spent hours walking along the beautiful white sandy beaches letting the topaz water tickle my toes. No one in sight. Heaven on earth! My husband enjoyed snorkeling and we sat on the beach and watched a glorious sunset.

Later that evening we enjoyed an exquisite dinner. Mouth watering delicious, from the Soupe de Tectec ((clam cooked in tomatoes, garlic and ginger), to the Gros Bourgeois de L’Ile Mahe (baked snapper with sauce), to the Cochon de lait rÙti (roasted pig), served with the Salade De Millionnaire (palmheart), followed by a Beignet de Giraumon (Pumpkin Donut), and last but not least the Ladob Patat.

We tried a few local restaurants during our three week holiday in the Sychelles, but always returned to Mrs. Man-Cham’s for the finest Creole Cuisine Seychelloise (a mix of Chinese, Indian, and French flavors).

On the morning of our departure, Mrs. Man-Cham presented me with a copy of her cookbook, 4th Edition 1973. I’ve treasured it all these years and often use her recipes.

Her son, Sir James R. Mancham became the Founding President of the Republic of Seychelles when the country became an independent sovereign State on the 29th of June 1976. Sometime later, I heard on the news that when he went to England, to attend the Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, he was deposed in a bloodless coup. A bloodless coup? Now that could only happen in paradise.

Originating in Genoa, farinata is a thin, nutty, peppery flatbread made with garbanzo bean (chickpea) flour. The French call it socca and in Tuscany it’s called cecina. In Uruguay and Argentina, it’s called fainá. It’s a delicious appetizer when seasoned with fresh rosemary, pepper, and sea salt, or topped with cheese and other tasty tidbits. But in Uruguay and in Argentina fainá is often paired with pizza and called horseback pizza, or pizza a caballo in Spanish. And nothing could be fainá.

Since Friday nights are home-made pizza night in our home (my husband makes a wicked crust), I’ve started making fainá to plop on top of slices of pizza.

You can find garbanzo bean flour (gluten free) at many natural food stores. In Uruguay, you can buy the mix in a package in the local supermarket. If you don’t have the mix, here’s a quick and easy recipe.

Preheat your oven to 450 degrees, or if in Uruguay set it on the hottest setting.

Ingredients:

2 1/2 cups garbanzo bean flour

1 teaspoon sea salt

7 tablespoons olive oil

2 tablespoons parmesan cheese (optional)

Freshly ground black pepper

2 1/2 cups water

Preparation:

Buen provecho!

I first arrived in Israel in 1968, following the ’67 Six-Day War, to learn Hebrew and study Jewish History at an ulpan on the border of the Negev and Judean Deserts, in the small settlement village of Arad (located a few kilometers west of the Dead Sea and 45 km east of Beersheba). I appreciated all the new things I was learning and the interesting foods I was being introduced to, but was shocked to learn that bagels didn’t exist in Israel. What? No bagels? How can I live and study here? How can Jews live without bagels? Being from LA, I often brunched at Canter’s Deli, the famous Jewish-style delicatessen in Fairfax. When it came to authentic bagels, I was spoiled.

The closest thing to a bagel, in Israel in those days, was a warm pretzel-looking object being sold by a street vendor … and sold only in the afternoon. I wanted a real NY bagel for breakfast with cream cheese, lox, sliced onion, and a slice of juicy tomato. So began my search for the perfect bagel recipe. I needed a chewy, dense mouth feel experience, and the local bread didn’t cut it.

A friend agreed to send a recipe by mail; one she’d found in the NYT’s food section. A recipe for “Authentic, classic, New-York style” bagels—which required kneading, rising, resting, forming, rolling, resting again, boiling, turning, and then baking. Since my small apartment didn’t come with an oven, I had to do the complex routine of making bagels on the top of a two-burner stove. It took several shopping trips to Beersheba to find all the ingredients, but I eventually did. Then I spent one entire day making and baking bagels. They were delicious—a gourmet edible masterpiece.

OMG, I thought later, no wonder Israelis don’t DO bagels. They’re too busy rebuilding their country. I decided to just get used to those warm pretzel-looking things. Instead of making bagels every week I helped plant trees in and around Arad.

When I visited Arad, many years later, the trees were standing tall and the warm pretzel-looking object tasted yummy. More bagel like than I remembered.

I had never tasted, and was totally unaware of, eggplant (one of the world’s healthiest fruits, well technically it’s a large berry), until I landed in the Middle East to live there in the late 60s. A few days after my arrival in Arad, Israel (a small village in the Negev Desert) a neighbor offered me a slice of warm pita bread and an Israeli dip made with roasted eggplant, tahini, and yogurt. “Yum,” I said, after my first bite, and reached out to sample it again, and again. I was hooked and asked for any and all eggplant recipes.

Years later while visiting the States, I went shopping for this royal purple, garden egg fruit. Not seeing it on display in the produce section, I asked for assistance. Forgetting the word for it in English, I asked for it using the Hebrew word —חָצִיל (hat-ze-leem). The produce man looked puzzled and asked me to describe it. I told him it was a fruit, eaten as a vegetable, sometimes substituted for meat, kind of egg shaped, with a heavenly purple, shiny skin. I then told him what it was called in French (aubergine), and in Spanish (berenjena). “Oh,” he said. “Eggplant!” and pointed to a display in a far corner of the produce section.

To this day, I still say חָצִיל (hat-ze-leem) in honor of my discovery of this amazing and delicious food—a must have in every Israeli or Middle Eastern meal. Back in the day, before ovens became a kitchen mainstay, many foods were cooked over an open flame. Gourmet chefs probably still stick a fork in the top end and slowly turn it until the skin is properly charred to give it a delicate smokey flavor. I find it equally delicious when roasted and charred in an oven. Over the years I have experimented with various eggplant recipes. Here’s one of my favorite.

Eggplant with Feta and Pine Nut Dip

Wash and dry two medium sized eggplants. Pierce both sides with a fork to vent, then place them on a lightly oiled (olive oil) baking sheet and broil or bake for 30-45 minutes (turning them once) until they are charred and soft to the touch.

Cool slightly and peel, carefully removing every bit of the scorched skin, Discard the charred skin. Cut in half lengthwise and scoop out the pulpy flesh and place in a bowl.

Crumble a big chunk (about 200 grams, 7 oz) of feta cheese into the bowl.

Add 1/4 cup olive oil

1 cup yogurt

1 T dried oregano leaves

3 chopped spring onions

1/2 cup pine nuts

… and anything else your heart desires or deserves. Stir to mix.

Serve with warm slices of pita bread.

תהנו! Enjoy!

I first arrived in Israel in 1968, following the ’67 Six-Day War, to learn Hebrew and Jewish History at an ulpan on the border of the Negev and Judean Deserts, in the small settlement village of Arad (located a few kilometers west of the Dead Sea and 45 km east of Beersheba). I appreciated all the new things I was learning and the interesting foods I was being introduced to, but was shocked to learn that bagels didn’t exist in Israel. What? No bagels? How can I live and study here? How can Jews live without bagels? Being from LA, I often brunched at Canter’s Deli, the famous Jewish-style delicatessen in Fairfax. When it came to authentic bagels, I was spoiled.

The closest thing to a bagel, in Israel in those days, was a warm pretzel-looking thing being sold by a street vendor … and sold only in the afternoon. I wanted a real NY bagel for breakfast. So began my search for the perfect bagel recipe. I needed a chewy, dense mouth feel experience, and the local bread didn’t cut it.

A friend agreed to send a recipe by mail; one she’d found in the NYT’s food section. A recipe for “Authentic, classic, New-York style” bagels—which required kneading, rising, resting, forming, rolling, resting again, boiling, turning, and then baking. Since my small apartment didn’t come with an oven, I had to do the complex routine of making bagels on the top of a two-burner stove. It took several shopping trips to Beersheba to find all the ingredients, but I eventually did. Then I spent one entire day making and baking bagels. They were delicious—a gourmet edible masterpiece.

OMG, I thought later, no wonder Israelis don’t DO bagels. They’re too busy rebuilding their country. I decided to just get used to those warm pretzel-looking things. Instead of making bagels every week I helped plant trees in and around Arad.

When I visited Arad, many years later, the trees were standing tall and the warm pretzel-looking things tasted yummy.

Here’s a fun site on the history of bagels.