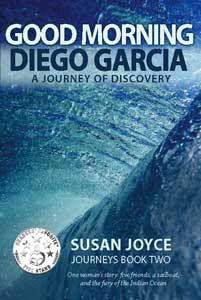

Trincomalee, Sri Lanka 1975

She grabbed my hand and practically pulled me down the gangplank.

By the time we left the dock and walked along the main road to town, I could feel negative energy building and billowing around us. I stopped twice; once I suggested we go back to the boat.

“Why?” Mia asked.

“So you can change clothes; show respect for the local culture.”

“It’s not my culture,” Mia retorted. “And I’m not local.” She kept walking.

I trailed behind with a growing feeling of dread.

“Come on,” she said. “I want to show you something.”

By the time she neared the entrance to the souk, word had spread about an indecently dressed woman walking the main street in the direction of the souk. An angry, vocal mob awaited her arrival.

I stopped again. Mia shrugged her shoulders and motioned me to hurry up. She was in a defiant mood and seemed clueless to the mounting danger.

“Mia,” I begged. “Please go back to the boat.”

“Why should I?” she yelled back.

“They’re angry at you.”

“Why?” She tossed her long, dark hair aside and kept strutting toward the entrance.

“Because of the way you’re dressed.”

“I don’t care,” she announced, walking on laughing.

As hostility swelled, the crowd grew larger. More villagers joined to show their support.

I stopped every few feet, hoping to reverse this scene.

When Mia reached the main entrance, the crowd surrounded her and began heckling her. They blocked her from entering the souk.

Whap! I heard the loud thud of a rock hit a wall. And another Whap! “Oh my God,” I gasped. They’re attacking her.

Whap! Zap! Thud! I heard Mia scream. The villagers were hurling sticks and stones at her.

“Run,” I yelled, “back to the boat.”

Whap! Whap, whap, whap! Mia screamed again. I saw her turn and push people aside.

“Run!” I shouted.

She took off running in the direction of the harbor, with the crowd chasing close behind. They continued to pelt her with whatever they could pick up and throw.

I slowed to a stop, took a deep breath, and covered my thumping heart with outstretched hands. I listened to my heart beat, and hoped Mia was outrunning the angry crowd.

The Tamil man from the cafe (where Charles and I had breakfast) was standing outside his restaurant as I passed by. He smiled and greeted me in English. “Your friend behaved badly,” he said. “Indecent exposure is against the law in Sri Lanka.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m sorry.” I shook my head, not believing what I had just witnessed. How could anyone travel the world (as she had) and not be aware of local customs in different countries. A total lack of respect. Chutzpah, as they say in Israel.